Following an earlier dispute over a trademark relating to a certain caterpillar cake, Marks and Spencer PLC (M & S) and Aldi Stores Limited have recently come to blows over another area of intellectual property; namely, Registered Designs. A recent judgement of His Honour Judge Hacon sitting in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court, High Court of Justice ([2023] EWHC 178 IPEC), has considered whether the advertising and sale of Aldi Christmas gin bottles infringes UK Registered Designs belonging to M & S.

This decision has interesting implications for “copycat” products relying on minor differences to avoid design infringement, and highlights a potential difference between UK Registered Design Rights and the Registered Community Designs available in the EU.

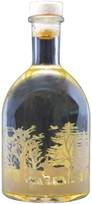

The Registered Designs in question protect bottles for gin-based liqueurs that are festively decorated and have an LED light in the base, which illuminates the contents of the bottle when turned on. The liqueur contains gold flakes, which become suspended in the liquid when the bottle is shaken. Illustrations of two of the designs in suit are shown in the first four images. The Aldi bottles are shown below.

An assessment of whether a product infringes a registered design hinges on whether the product provides a different overall impression on an informed user relative to the design in suit. The judgement concluded that the similarities between the Aldi bottle and the designs in suit are individually significant, and cumulatively striking. In particular, the bottles and stoppers are identical in shape and a winter scene including tree silhouettes is provided over the entirety of the straight portion of the bottles. Furthermore, the Aldi bottle has a snow effect and an integrated light, both of which are included in the designs in suit. Although there are acknowledged differences between the Aldi bottle and the designs in suit, these are differences of relatively minor detail such as minor differences to colouring or to details of the pattern on the bottle. These small details do not affect the lack of difference in the overall impressions produced by the Aldi bottle and by the designs in suit, thanks to the striking common features.

It is notable that altering multiple minor details of a design has been judged to be insufficient to avoid infringing said design. This reinforces that determining the overall impression of the registered design is critical to any question of infringement, and that it is this overall impression that needs to be considered even in the face of multiple different details.

To determine this overall impression and whether a product provides a different overall impression multiple factors are taken into account including the design freedom available to the designer, and the design corpus of designs available to the informed user.

Design freedom

In making an assessment of whether a product provides a different overall impression than a registered design, the degree of freedom available to a designer is taken into account. If a product must include certain features, for example due to the nature of the product or due to technical limitations, then a product may require smaller or fewer differences in order to provide a different overall impression to the registered design.

In this judgement, it was found that if a snow effect was to be used, then technical constraints and legislation meant that the flakes must be gold. Otherwise, Hacon decided that the designer had considerable design freedom, particularly with regard to the shape of the bottle and the design printed on the bottle.

Notably, counsel for Aldi had argued that the light must be put in the base of the bottle. Although Hacon agreed that this was the only practical place to put a light, it was commented that this requires the choice of a light in the first place. As there is no design constraint to require the gin to be illuminated, the placement of the light does not constitute a lack of freedom of design.

Features solely dictated by technical function

When comparing a product with a registered design for the purposes of an infringement assessment, the court is required to ignore features solely dictated by technical function.

The counsel for Aldi argued that various features of the designs in suit were solely dictated by technical function, however it was decided that the features were aspects of or consequences of aesthetic choices made by the designer. For example, it was alleged that the use of gold for the flakes was solely dictated by technical function, as was the fact that said gold flakes are scattered in the liquid when the bottle is shaken and otherwise settled at the bottom of the bottle. It is true that if snow effect is used, the flakes must be gold and they must have the described distribution, but this does not give the gold flakes a technical function.

The fact that the decision to have a snow effect was not a technical one, but an aesthetic one, may have been important in this regard.

Grace period

The design corpus, i.e. the designs available to the informed user, does not legally have a bearing on the assessment of infringement. However, it affects the informed user’s comparison of the product and the design in suit. The more strikingly different the registered design is from the design corpus, the more likely it is that a product having some of the same unusual features will produce the same overall impression as the design in suit. It is therefore important to determine what the design corpus contains. It may be particularly relevant to determine whether the design corpus contains previous designs disclosed by the proprietor.

The designer of a registered design is accorded a grace period of 12 months in which they may disclose the design without such disclosure being considered relevant to the novelty or individual character of that design when they come to register the design. This section of the law refers to the validity of the design. However, this judgement states that the grace period also applies in the context of infringement. Therefore, any such disclosure by the designer that would be considered to be excluded from being a prior disclosure for the purposes of validity is also excluded from the design corpus that is relevant to an assessment of infringement.

The judgement goes on to consider the question of whether a disclosure by the designer during the grace period is excluded from being a prior disclosure only if it is specific to the registered design in suit, or whether the same applied to other similar designs disclosed by the designer during the grace period. The judgement refers to the rationale for the grace period, which is to allow a designer to trial designs before applying for a registered design. By this reasoning, it was decided that a disclosure of any design by the designer during the grace period is excluded from being a prior disclosure for validity, and from the design corpus for infringement.

Description

The scope of protection of a registered design depends on what is shown in the image of the design as registered. In rare occasions, such as this case, there may be issues in interpreting the image. Here, the issue is whether each of the registered designs has an integrated light in the base of the bottle.

For both Community Designs and UK Registered Designs, the indication of the intended product is irrelevant to the scope of protection (Art. 36(6) Regulation 6/2002 and Rule 5(5) Registered Design Rules 2006, respectively). Community designs go further, and it is explicitly stated that any description provided with a design is irrelevant to the interpretation of the designs. For UK Registered Designs this is less clear, since Rule 5(5) says nothing about the description.

Providing a description is optional. In this case, the registered designs in suit each contain the description “Light Up Gin Bottle”. In this judgement, Hacon has commented that whereas the description is not shown on the public register of Community Designs, if an applicant provides a description for a UK Registered Design that description may appear on the public register. He goes on to say that if the description is irrelevant to the interpretation of a UK registered design, there is a possibility that members of the public consulting the public register may be misled. When seeking to resolve an ambiguity in the image shown, members of the public may be given a steer by the description.

Here, Hacon has relied on the images and has decided that two registrations show the integrated light feature and two do not without relying on the description. However, it is interesting to note that the description having an effect on the scope of protection was not ruled out, which may lead to a marked difference between registered designs in the UK and the EU. Applicants should carefully consider the effect that any description filed with a UK design application may have on the scope of protection.

Conclusion

This judgement has provided useful examples on how to interpret the overall impression of a registered design and a potential infringement, particularly with regard to design freedom and technical function. Confirmation has also been provided that the grace period applies to infringement, and that it covers any design disclosed by the proprietor during the grace period.

A potential divergence between UK Registered Designs and Community Designs has been highlighted, whereby the description of UK Registered Designs may be relevant to the scope of protection if assessing the image leaves ambiguities. In light of this, applicants may wish to give some thought to whether they provide a description, and the wording of the description if provided.

This case has implications for the manufacture and sale of “copycat” products. Based on the success of M & S in this case, more proprietors of registered designs may hope to successfully argue that despite a number of small differences, the overall impression of a potential infringement is the same.