The first Unified Patent Court (UPC) decision (Plant-e v. Arkyne) discussing the doctrine of equivalents has recently published.

In the decision, the Hague local division of the UPC found Plant-e’s patent to be valid and infringed by Arkyne. As a result, Arkyne were ordered to cease infringement and withdraw their products from market in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

The comments in the decision regarding infringement are the most interesting. After finding that there was no literal infringement (because not all claim features were present in the alleged infringement), the court assessed whether there was infringement within the doctrine of equivalents. The court proposed a four-step test which they followed in their assessment, and concluded that there was infringement. This four-step test provides useful guidance to how such issues might be treated by the UPC in future.

Technology

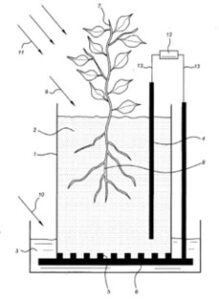

Plant-e’s patent EP 2 137 782 relates to a device and method for converting light energy into electrical energy using a living plant. The plant converts light energy into feedstock for a microbial fuel cell (see the image below right).

The claim at issue was independent method claim 11, which recited a:

“Method for converting light energy into electrical energy and/or hydrogen,

wherein a feedstock is introduced into a device that comprises a reactor,

where the reactor comprises an anode compartment (2) and a cathode compartment and

wherein the anode compartment comprises

a) an anodophilic micro-organism capable of oxidizing an electron donor compound, and

b) a living plant (7) or part thereof, capable of converting light energy by means of photosynthesis into the electron donor compound,

wherein the microorganism lives around the root (8) zone of the plant or part thereof.”

(Photo: from patent EP 2 137 782 )

Arkyne’s Bioo panel (shown below) is a ‘biological’ battery including a bottom compartment provided with a cathode (4) and an anode (5) separated by soil. The Bioo panel also includes a top compartment containing soil, plants and the plants’ roots. The Bioo panel was advertised as being capable of generating an electric current through anodphilic micro-organisms near the anode that oxidise feedstock in the soil. Chemical energy of organic material in the soil, and generated by the plants via photosynthesis, is then converted into electrical energy.

(Photo: Arkyne’s Bioo panel datasheet, UPC decision)

Literal infringement

The court first discussed literal infringement of the patent. Two claim features were in dispute – was there a living plant present in the Bioo panel and were the micro-organisms present around the plant’s roots?

Arkyne attempted to argue that a plant was not essential to the function of the Bioo panel, and it could function with soil alone. However, this was dismissed by the court. Also, the court agreed it was apparent that the plant and its roots were surrounded by soil which contained the (naturally occurring) micro-organisms.

Plant-e’s patent taught that the plant and its roots should be located in an anode compartment. In contrast, the plants and their roots in the Bioo panel were located in the top compartment, while the anode was provided in the bottom compartment. As such, the court ruled that there was no literal infringement.

Doctrine of equivalents

The court then considered the doctrine of equivalents. In particular, whether the setup of the Bioo panel, with the plants and roots in a top, non-anode, compartment was equivalent to the method of claim 11 of the patent that required the plant and its roots to be in the anode compartment.

In its review, the court used a test to determine whether the variation found in the Bioo panel should be regarded as an equivalent based on the approach of ‘several national jurisdictions’ – in order for a variation found in an alleged infringement to be regarded as an equivalent, the answer to each of the four following questions must be yes:

1) Technical equivalence: does the variation solve (essentially) the same problem that the patented invention solves and perform (essentially) the same function in this context?

2) Is extending the protection of the claim to the equivalent proportionate to a fair protection for patentee in view of the contribution to the art and is it obvious to the skilled person from the patent publication how to apply the equivalent element (at the time of the infringement)?

3) Reasonable legal certainty for third parties: does the skilled person understand from the patent that the scope of the invention is broader than what is claimed literally?

4) Is the allegedly infringing product novel and inventive over the prior art (i.e., there should be no successful Gillette/Formstein defence)?

1) Technical equivalence

The teaching of the patent was to create a microbial fuel cell independent of externally supplied fuel. This was achieved by using a living plant in the system to supply organic material to generate an electrical current between the anode and cathode.

Experiments on the Bioo panel showed that water, nutrients and micro-organisms in the upper compartment would pass through a filter into the lower compartment where they would also generate an electrical current between the anode and cathode. Hence, the court found the setup of the Bioo panel to be technically equivalent – the plant in the Bioo panel had the same function, the only difference being its location in an extra compartment which didn’t affect the function.

2) Fair protection for patentee

The court considered the invention to provide a new category of microbial fuel cells and therefore determined that a fairly broad scope of protection was in line with the contribution to the art.

3) Legal certainty for third parties

The court noted that legal certainty was met if the skilled person understood that the claim left room for equivalents because the patent’s teaching was clearly broader than the claim wording and there was no good reason to limit the scope to that of the claim.

The court ruled that the patent’s teaching was clearly broader than the claim– it taught to add a plant to a microbial fuel cell to provide a fuel source for the cell so as to make the cell independent of an externally provided feedstock, and the skilled person would understand the Bioo panel variation to be another way of obtaining the same result.

4) Novel and inventive over the prior art?

The court confirmed that the Bioo panel would have indeed been novel and inventive at the priority date (due to the first use of a plant to supply the fuel). This question also provides a useful reminder about the Gillette or Formstein defence for infringement (see our bulletin here for more details), i.e., if the alleged infringement is not patentable over the prior art cited against the patent, then the patent must be invalid.

Takeaway

This decision provides the first guidance from the UPC as to how to assess infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

It is noted that this is only a first instance decision and if this case, or a similar case, was to be appealed, the UPC Court of Appeal might provide its own opinion on the doctrine of equivalents. That said, it is encouraging that the court’s approach appears quite sensible (and is very similar to the test developed by the Hague Court of Appeal in 2020 – see here (in Dutch)), and so it would be surprising if a Board of Appeal departed wildly from the four-step test. Watch this space!